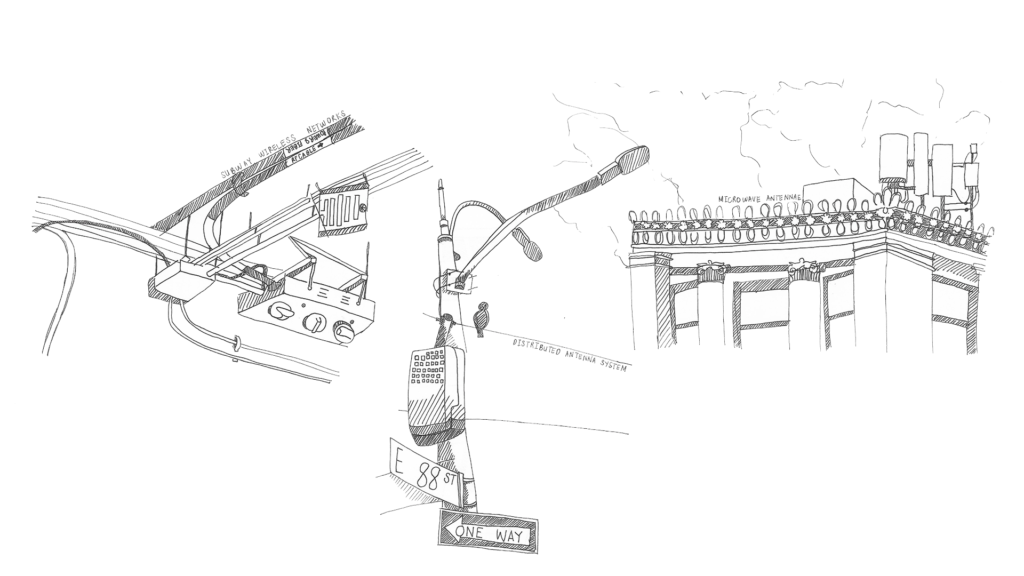

After reading Ingrid Burrington’s field guide to networks in NYC, I couldn’t unsee the devices and ‘marks’ of network as I moved around the city. Here are the memorable ones that I thought stood out from my routine path–– for different reasons.

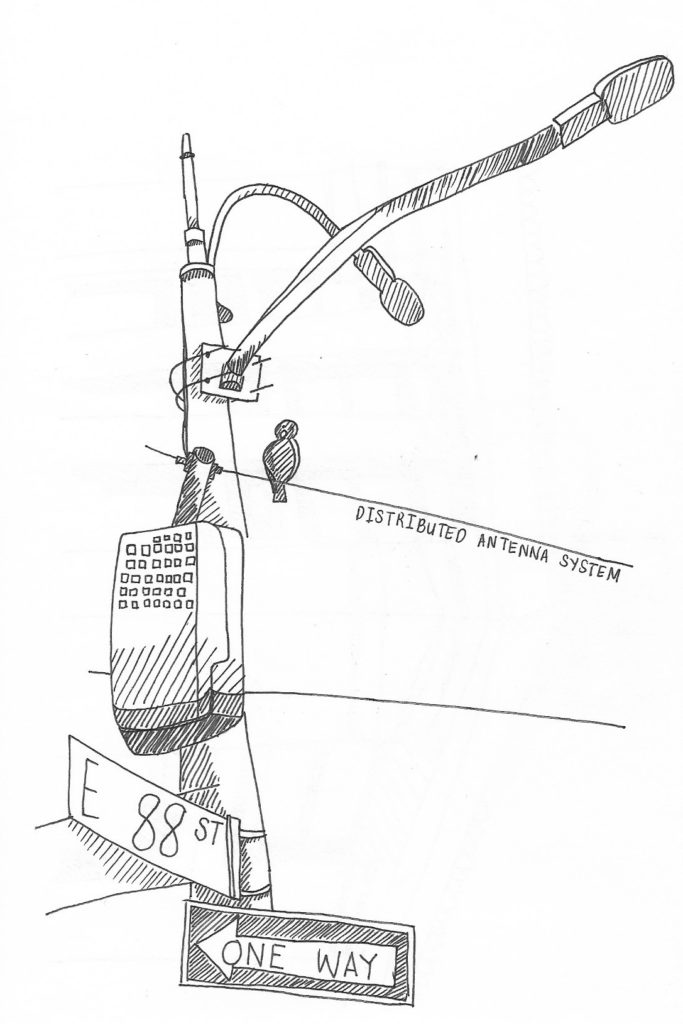

As i was walking to the 86th Street station, I noticed that one of the street lamps had added height to it. I recognized it, having read about it in the guide but did not remember what it was called so I took a picture of it to research on later.

Distributed Antenna System (DAS) • Helps distribute signal in under-covered areas; connected to fiber optic networks underground.

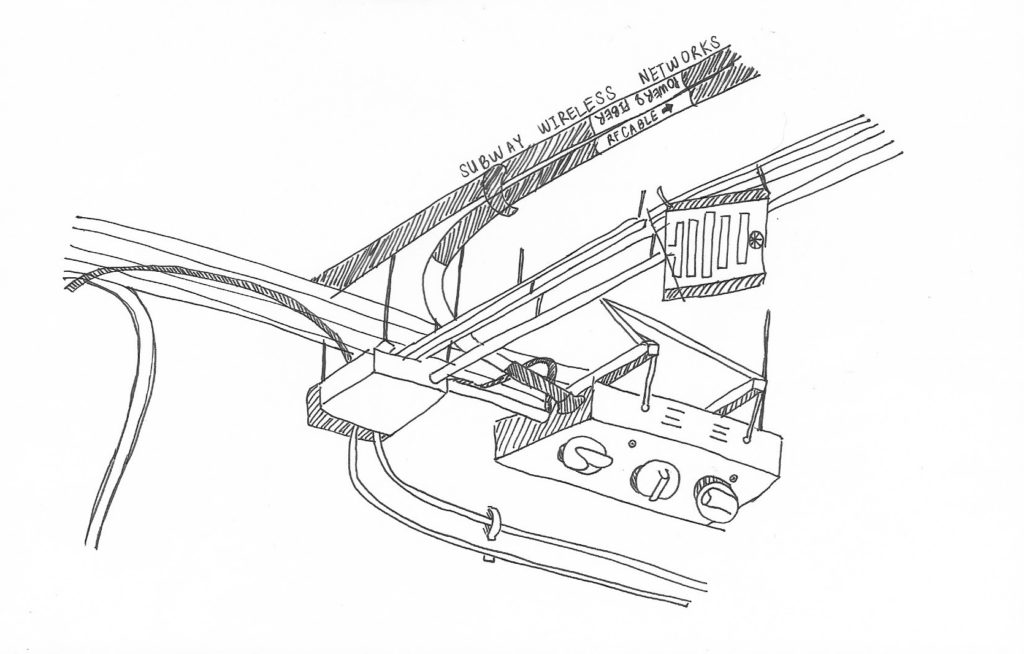

Last month, I noticed right above the spot where I wait for the 6 train, that there were knobs marked with “DO NOT PAINT” in bold. I wondered then, why it was so important not to paint over these knobs– having no clue what they controlled or if they even moved at all.

Seeing this in the guide gave me an aha! moment:

Subway wireless networks • Provides wifi connectivity underground

The big tubes are labelled “RF CABLE” and “POWER AND FIBER”, suggesting where and how the device is connected. RF stands for radio frequency– I inferred this based on the guide. Apparently the signals from the base station (home base) are distributed to the connected stations via these fiber optic cables and converted into RF signals.

**Subway wireless networks- also a DAS!

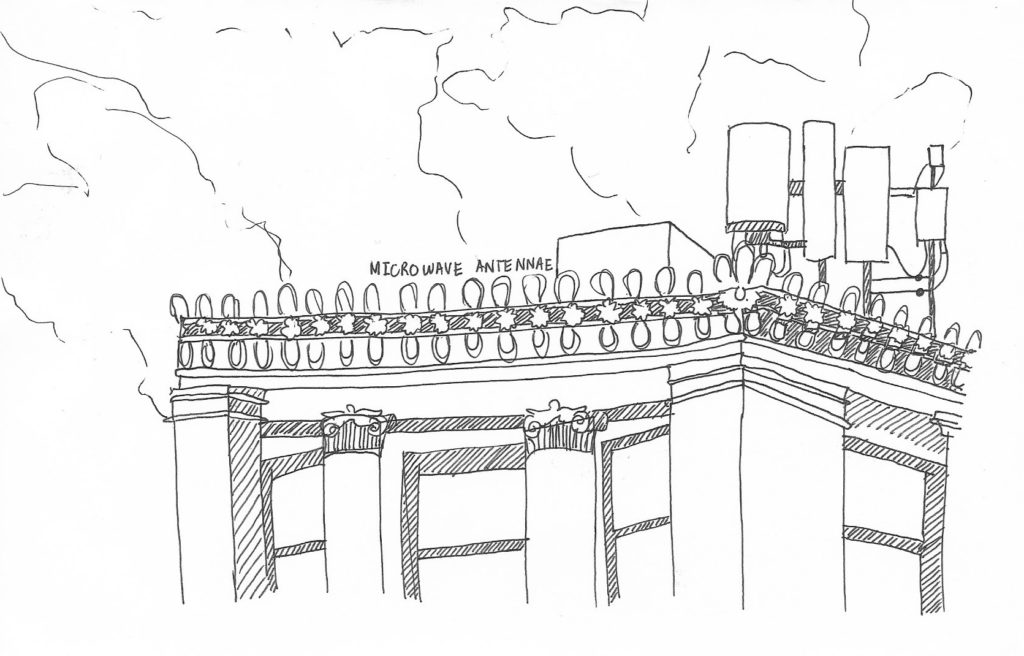

Before grabbing dinner with some friends in the East Village, I got some work done. While staring out the window of Parsons’ library, I recognized yet another piece of network infrastructure– the microwave antenna– affixed on the rooftop of another Parsons building across the street (5th Ave).

Microwave Antenna • Wireless internet service provider that provides broadband services through a network of antennae

I like the contrast between the clunky device that seems to be reaching up and out and the classical style, architectural building that seems to have been there for decades, standing still.